Abstract

Background

The burden associated with the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) is expected to increase due to the aging population. Thus, policymakers and clinicians need a holistic view of the healthcare resource use (HCRU) and costs associated with MM and its treatment for informed decision making. However, nationwide information on HCRU and costs due to MM is scarce in Finland. The aim of this study was to determine healthcare resource utilization, patterns of service use and associated costs among Finnish patients with MM during the first 5 years from their first diagnosis and at end of life.

Methods

Data on patients newly diagnosed with MM and receiving treatment for it in Finland in 2015–2019 was sourced from comprehensive nationwide registers. Data on all-cause and MM-specific HCRU including inpatient stays, outpatient visits and contacts, emergency care visits and home care were obtained separately from specialized and primary care registers. HCRU costs were assessed by multiplying the numbers of primary and specialized care contacts by respective national unit costs. For reimbursed outpatient medication and reimbursed sick leave, data on actual costs were collected. All registry data were linked via unique personal identifiers, and follow-up time was up to 5 years.

Results

Altogether, 1615 patients were included in the analyses. In the 5-year follow-up period, patients had on average 96 healthcare contacts per patient-year (PPY) and the mean all-cause healthcare costs were €46,000 PPY. Around 47% of these costs originated from reimbursed outpatient medication and the rest from healthcare contacts. Over half (60%) of the contacts occurred in primary care but most of the costs were associated with specialized care. Additionally, 29% of contacts were MM-specific, but they were responsible for 58% of the costs. The HCRU was highest during the first year after diagnosis, levelled off during the follow-up and then increased significantly during the last year of patients’ lives. The number of all-cause healthcare contacts PPY was approximately 53% higher, and the respective costs were 5% higher during the last year of a patient’s life when compared with the first year after diagnosis. During the last 12 months (N = 417) and 6 months (N = 505) of life and during palliative care (N = 145), the most common healthcare contact was home care.

Conclusions

During active treatment, MM is primarily treated in the specialized care setting, with outpatient medication and visits to specialized care being the main cost drivers. These results can be utilized to estimate the need for care and expected costs over time due to MM and in health economic evaluations concerning MM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Healthcare resource use and associated costs of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) in Finland are the highest during the first year after diagnosis and during the end of life, with the focus in care shifting from the specialized to primary care setting. |

MM imposes a significant burden on both primary care and specialized care in Finland, which is likely to increase due to an aging population. |

The results highlight the importance of a holistic view of real-world data studies within a healthcare system and especially in a disease that mainly affects older people with multimorbidity. |

1 Introduction

Despite the evolvement of care and introduction of multiple new therapies and treatment options during recent decades, multiple myeloma (MM) is currently considered incurable [1]. In our previous study in Finland [2], we presented a median overall survival (OS) of 4.5 years for patients with newly diagnosed MM in 2015–2019. Multiple myeloma disproportionately affects the elderly, with a median age of 71 years at diagnosis [2]. The annual crude incidence was on average 8.8 while the crude prevalence at the end of 2019 was 32.7 cases per 100,000 in the population aged 18 years or older. The age-standardized (WHO World Standard Population [2000–2025]) incidence was estimated at 3.3 per 100,000. Despite the relatively stable age-standardized incidence [2], the number of new patients with MM is increasing due to the aging of the population. Thus, information on the expected resource use and healthcare costs among patients with MM in different phases of the disease is essential when evaluating the burden of MM to healthcare systems in the future.

Overall, healthcare costs associated with the care of patients with cancer are substantial, with costs and cost drivers differing across various phases of the disease. Based on existing literature [3,4,5,6], the costs of cancer follow a U-shaped curve, the greatest costs occurring during the initial and terminal phases of care. European studies on MM suggest that the key drivers of healthcare costs during the active treatment phase are medication and inpatient stays [7,8,9,10]. However, the estimated annual costs due to MM vary across studies.

A Danish nationwide study compared the mean annual healthcare costs (outpatient services, inpatient admissions, prescription drugs and primary health sector costs) of MM patients diagnosed in 2002–2005 (n = 1531) and 2010–2013 (n = 1972) [8]. Patients were stratified by age (<65 years or ≥65 years) and followed up for a maximum of 3 years onwards from the diagnosis. The estimated total annual healthcare cost per patient decreased from €51,000 to €44,000 in younger patients and increased from €27,000 to €31,000 in older patients between the time periods. In both age groups and time periods, the estimated annual costs decreased after the first year of follow-up. A French study of around 6400 patients diagnosed and treated for MM in 2013–2018 estimated the mean annual costs of disease (including healthcare costs, sick leave, disability pensions and transportation) per patient at €72,000 for the first year after diagnosis [7]. Over the whole follow-up (median: 22 months), the respective mean annual costs were €58,000 per patient. A Portuguese study of 1941 patients with prevalent MM reported that the average annual direct healthcare costs per patient were €31,000 in 2018 [9]. In a Finnish study of patients diagnosed and treated for MM in one large hospital district in 2013–2019, the average specialized care costs per patient-year were estimated at €33,000 and €20,000 for those treated with and without stem cell transplantation (SCT), respectively [11].

Cost-effectiveness analyses for new therapies are often carried out using a lifetime approach where all costs and benefits associated with different treatment options are estimated throughout a patient’s lifecycle, that is until death. Thus, the interest in end-of-life resource use and associated costs in MM has increased as well; however, the evidence is scarce, particularly in Europe. A single-center study conducted in the Netherlands in 2017–2021 estimated that the cost of hospital care during the last month of life was around €8000 per MM patient [12]. Inpatient stays and intensive care were the key cost drivers. The average end-of-life costs of hospital care were highest among patients who died within 5 years from diagnosis. In general, the end-of-life costs of patients with MM were higher compared with those of patients with other malignancies.

In Finland, every permanent resident is entitled to publicly funded healthcare services. Public health services are divided into primary care and specialized healthcare. Primary care services are generally provided by social and healthcare centers, and they include counseling, outpatient services in general medicine, oral healthcare and rehabilitation. Specialized healthcare services include diagnosis and treatment by clinical specialists, and they are mainly provided by hospitals and their outpatient clinics. Access to specialized hospital care is organized through a tiered treatment system with specific criteria and usually requires a referral.

After the implementation of the Finnish social and healthcare reform on Jan 1, 2023, the responsibility for organizing healthcare, social welfare and rescue services was transferred from over 300 municipalities and joint municipal authorities to 21 wellbeing services counties and the City of Helsinki. The wellbeing services counties are self-governing and responsible for adequate funding and allocation of healthcare services [13]. For example, medicines administrated in hospitals are acquired and funded by the wellbeing services counties whereas outpatient medicines dispensed at community pharmacies are paid by the patient and reimbursed by the Social Insurance Institution (Kela) if the medicine is under the national reimbursement scheme.

The treatment pathway for patients with MM in primary and specialized healthcare in Finland can vary according to the patient´s condition and characteristics, the stage and severity of the disease and the treatments provided. As we have previously presented, patients diagnosed with MM in Finland have multimorbidity and often have comorbidities mainly treated in the primary care setting [2]. Therefore, a holistic view of the total burden and costs associated with the treatment, healthcare resource use (HCRU) patterns, end-of-life care and palliative care of patients with MM in Finland is needed. Specifically, after the recent restructuring of healthcare organization in Finland, the newly established wellbeing services counties work under a fixed budget. This means that both the decision makers and care providers need to consider the costs associated with treating versus not treating patients and weigh their decisions against potentially achievable health gains.

To help fill gaps in the current knowledge, the aim of this nationwide register-based study was to determine all-cause and MM-specific healthcare resource utilization, patterns of service use and associated costs in Finnish patients treated for MM during the first 5 years from their first diagnosis, before end of life and during palliative care.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Sources

Data were sourced from comprehensive registers of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), the Social Insurance Institution (Kela) and Statistics Finland that cover all ~5.6 million residents of Finland. Personal identifiers unique to every resident of the country were used for data linkage. Data on inpatient stays in primary and specialized care and outpatient visits in specialized care, including emergency care visits, were obtained from the THL Care Register for Health Care (Hilmo). Data on primary care visits in the public sector, including home care, were obtained from the Register of Primary Health Care Visits (AvoHilmo) of THL. Data on reimbursed outpatient medicine purchases at community pharmacies came from the Finnish Prescription Register of Kela, data on sick leave came from the Kela Register for Seasonal Benefits and date of death from Statistics Finland.

2.2 Study Design and Population

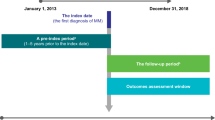

A retrospective cohort design was used to address the study objectives. The study population was a sub-cohort of a previously identified cohort of 2037 patients with newly diagnosed MM in Finland in 2015–2019 [2]. Briefly, the main cohort included patients ≥18 years of age with their first Hilmo record specific to MM (identified with International Classification of Diseases, 10th Version [ICD-10] code C90.0) in 2015–2019. Furthermore, the patient had to have at least one Hilmo record with C90.0 as the primary diagnosis during 2015–2019 and at least two additional Hilmo records with C90.0 at any diagnosis position by the end of 2020. The present study included those 1615 members of the main cohort who had any of the following register markers for receiving MM-specific treatment between their first recorded MM diagnosis and the end of 2020: (1) a reimbursed purchase of outpatient MM medicines, (2) a Hilmo record with any code for radiotherapy in association with ICD-10 code C90.0, (3) a Hilmo record indicating SCT. A detailed description of codes used for identifying each treatment from the registers and a flowchart of cohort formation are presented in Ruotsalainen et al. 2023 [2].

2.3 Outcomes and Analyses

Three sets of analyses were conducted: (1) description of baseline characteristics of the study cohort, (2) description of all-cause and MM-specific HCRU and costs for each year of follow-up for the first 5 years since the index date and (3) description of end-of-life HCRU and costs for patients who died during the follow-up and separately for patients who died during palliative care.

2.3.1 Baseline Characteristics

Patients were characterized by age, sex and comorbidity. Age and sex were measured at diagnosis. Comorbidity was captured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which was calculated using the adaptation of the CCI for register-based studies by Ludvigsson et al. [14]. Comorbidities included in the CCI were identified from both Hilmo and AvoHilmo over a 4-year look-back period preceding the first diagnosis. That is, the data for measuring comorbidities covered the years 2011–2019.

2.3.2 Assessment of Resource Use and Costs

The utilization of healthcare resources was evaluated separately for primary care and specialized care. For primary care, numbers of outpatient visits (any), inpatient stays, home care and other contacts (call, consultation, electronic transaction etc.) were counted. For specialized care, numbers of emergency care visits, other outpatient visits and inpatient stays were counted. An HCRU item was defined as MM-specific if the MM diagnosis appeared as the primary diagnosis (ICD-10 code C90.0 in Hilmo, ICD-10 code C90.0 or ICPC-2 code B74 in AvoHilmo).

The cost of care was assessed using respective national unit costs [15] for observed resource use. Primary care contacts were grouped by type (visit, call, home care, etc.), service area and healthcare professional. The costs of outpatient visits and inpatient stays in specialized care were calculated by using average costs of each contact type in each specialty area (e.g., oncology or internal medicine). The unit costs of outpatient visits and inpatient stays include salaries, materials, in-hospital medication and procedures and examinations performed in primary or specialized care. When a specific unit cost for a healthcare contact could not be determined, the lowest applicable price was chosen. All unit costs were inflated to 2022 values using the national healthcare price index from Statistics Finland (2023) [16].

The actual total costs of reimbursed outpatient medication, including both paid reimbursements and patient copayments, were available from the Finnish Prescription Register of Kela. MM-specific medication costs refer to the outpatient costs of lenalidomide, thalidomide, pomalidomide, ixazomib, melphalan, dexamethasone, prednisolone and prednisone when reimbursed to the patients with a reimbursement code for malignant hematological diseases. All-cause medication costs include total costs of all reimbursed outpatient medicine purchases of the patient. In Finland, there is an annual copayment (ceiling ~€600 during the study period) to protect patients from high cumulative copayment expenditure. Copayments of all reimbursable outpatient medicines, regardless of their indication, count towards the ceiling. Therefore, Kela’s social security covers the majority of the medication costs reported in this study. Finally, the actual costs of reimbursed sick leave days were available from the Kela Register for Seasonal Benefits. Sick leave was considered MM related when MM was the main diagnosis for the leave.

In this study, the expression ‘HCRU costs’ refers to costs associated with healthcare contacts, and ‘healthcare costs’ include HCRU costs and reimbursed outpatient medication costs. Sick leave costs were analyzed separately. Other cost elements, such as transportation or productivity losses due to disability pensions, were not included in the analyses.

The study cohort was followed-up from the first diagnosis until the administrative end of the study (December 31, 2020) or death, whichever came first. For the whole study cohort, all-cause and MM-specific HCRU contact counts and associated costs, reimbursed outpatient medication costs, as well as sick leave days and associated costs per patient-year (PPY) are reported for each of the first 5 years of follow-up from diagnosis (0–1 = first, 1–2 = second, 2–3 = third, 3–4 = fourth, 4–5 = fifth). For patients who received palliative care, the respective figures are reported for the period from the initiation of palliative care until the date of death, and for those patients who had a minimum follow-up of 6 or 12 months from diagnosis, for the last 6 or 12 months of life, respectively. For the end-of-life cohorts, all-cause and MM-specific resource use and costs were assessed per patient-month (PPM).

2.4 Statistical Analyses and Other Considerations

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1 or newer for Linux. For any subgroup with n < 5, the data are not shown and hence neither HCRU nor cost analyses were conducted, in accordance with the policies of the data protection authority. Due to data structure changes in Hilmo, the variable ‘contact type’ was missing for 52% and 85% of observations in specialized care in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Therefore, missing values for this variable were imputed by assuming that the distribution of the contact type (emergency care visit, other outpatient visit or inpatient stay) within each specialty remained the same as in the data from years 2015–2018 with known contact type values. Imputation was carried out separately for MM-specific contacts and non-MM-specific contacts, and contacts during the first year of follow-up and later contacts. For primary healthcare contacts missing data on the variable ‘healthcare professional’, the lowest unit cost per contact type and service area were used.

3 Results

3.1 Study Cohorts

In total, 1615 patients diagnosed with MM during 2015–2019 were included in the analyses. The mean age of the study cohort at diagnosis was 69.5 years, 29.5% were <65 years of age and 51.6% were male (Table 1). The average level of comorbidity measured by the CCI was 1.64. The cohort accumulated a total of 4387 patient-years during the first 5 years from diagnosis, the median follow-up time being 30.9 months. With respect to the end-of-life analyses, 417 and 505 patients were available for the analyses covering the last 12 and 6 months of life, respectively, with the median survival of 28.8 and 25.1 months. The number of patients who received palliative care before death was 145, which accounted for 25.1% of the 577 patients who died by the end of 2020, the mean time in palliative care being 2.6 months. Among these patients receiving palliative care, the median survival time from the first diagnosis was 30.8 months.

3.2 Healthcare Resource Utilization and Service Use Patterns During the First 5 Years From Diagnosis

During the entire 5-year follow-up period, patients had on average 95.9 healthcare contacts per patient-year (PPY). More than half (59.5%) of total HCRU were in primary care, driven by home care visits. Less than one third (28.8%) of all HCRU were MM-specific. A large share of MM-specific healthcare contacts focused on specialized healthcare, accounting for around 84–92% of all specialized healthcare contacts during each year of follow-up (Table 2). A vast majority of all-cause (88–91%) and MM-specific (91–97%) specialized healthcare contacts were outpatient visits.

The number of total annual HCRU from any cause was highest during the first year from diagnosis (117 contacts PPY) (Table 2). The lowest number of contacts was observed during the third year (78 contacts PPY). After this, the number of contacts increased slightly up to 88 contacts PPY during the fifth year. There was a downward trend in the share of MM-specific healthcare contacts of total all-cause HCRU (34% in the first year and 24–27% in the following years). The highest relative decline was observed with MM-specific inpatient stays, the average number of which (PPY) reduced around 80% after the first year from diagnosis. Interestingly, the share of MM-specific inpatient stays decreased more in the specialized care setting.

3.3 Healthcare Resource Utilization and Service Use Patterns Before End of Life and During Palliative Care

All-cause and MM-specific HCRU per patient-month (PPM) during palliative care and the last 12 and 6 months of life are presented in Table 3. Within the last 12 and 6 months of life and during palliative care, patients had on average 15, 17 and 19 all-cause healthcare contacts PPM, of which 19%, 17% and 12% were MM-specific, and primary care accounted for 77%, 76% and 87% of the total HCRU, respectively. The most common healthcare contact was home care, accounting for 64%, 62% and 71% of all HCRU in the last 12 and 6 months and during palliative care, respectively. All-cause HCRUs increased towards a patient’s end of life in the primary care setting where, excluding inpatients stays, a minority of the contacts were defined as MM-specific. All-cause HCRU in specialized care during the last 6 months increased slightly compared with the last 12 months but decreased towards the time in palliative care. The decrease in all-cause specialized care contacts during palliative care was mainly driven by a decrease in outpatient visits.

When converting the number of healthcare contacts PPM to contacts PPY, patients had on average 179 all-cause healthcare contacts, 137 primary care contacts and 42 specialized care contacts during the last 12 months of their life. When comparing the HCRU in the last year of a patient's life to the first year after MM diagnosis (Table 2), the number of total all-cause HCRU PPY increased by 53%, with an increase of 109% in all-cause primary care contacts and a decrease of 17% in all-cause specialized care contacts.

3.4 Healthcare Costs During the First 5 Years From Diagnosis

The mean healthcare costs were €46,000 PPY during the 5-year follow-up and 70% of the costs were MM-specific. Around 47% of all-cause and 57% of MM-specific costs originated from reimbursed outpatient medication and the rest of the costs from HCRU. The share of outpatient medication costs varied from 31% of all-cause and 36% of MM-specific costs during the first year of follow-up to 60% and 73% during the fifth year of follow-up. Both all-cause and MM-specific annual healthcare costs were the highest during the first year from diagnosis; €53,000 PPY and €36,000 PPY, respectively (Fig. 1). The lowest all-cause and MM-specific costs were observed during the third year of follow-up, after which the costs increased constantly.

The mean HCRU costs PPY during the 5-year follow-up period were €25,000 and 58% of the costs were MM-specific. The costs were the highest within the first year of diagnosis (€37,000 PPY), being approximately twofold compared with the following years (Fig.1). Within the first year of diagnosis, 63% of the HCRU costs were MM-specific, with the share reducing to 48%–52% in the following years. Although most all-cause healthcare contacts focused on the primary care setting, specialized care was responsible for most of the all-cause HCRU costs, accounting for 86% (€31,000 PPY) of the total HCRU costs in the first year, and approximately 79% (€14,000–€15,000 PPY) of the total HCRU costs during the following years. In particular, although it was the most common all-cause healthcare contact, home care in the primary care setting only accounted for 5–9% of the all-cause HCRU costs PPY during the follow-up. The main cost drivers in both all-cause and MM-specific HCRU costs were outpatient visits and inpatient stays in specialized care. Within the total MM-specific HCRU costs, the share of specialized care costs ranged between 92% and 94% during the 5-year follow-up, driven by specialized care outpatient visit costs.

During the 5-year follow-up period, the total mean costs of reimbursed outpatient medication PPY were approximately €22,000, of which 86% were MM-specific. Lenalidomide accounted for 75% of total reimbursed outpatient medication costs, followed by pomalidomide with 8% (Supplementary Table 1, see electronic supplementary material [ESM]). During the first year from diagnosis, the total costs of reimbursed medication PPY were €16,000, increasing to €24,000 for the second year from diagnosis, and to €28,000 for the fifth year from diagnosis (Fig 1). During the first year from diagnosis, lenalidomide accounted for 77% (€19 million total/€13,000 PPY) of total reimbursed medication costs, with the share increasing to 82% (€24 million total/19,000 PPY) during the second year from diagnosis. The mean PPY costs and the share of the total costs of lenalidomide began to decrease after the second year of diagnosis, being €18,000 (75%), €17,000 (66%) and €16,000 (57%) in the third, fourth and fifth year from diagnosis, respectively.

3.5 Healthcare Costs Before End of Life and During Palliative Care

The mean healthcare costs PPM within the last 12 and 6 months of life and during palliative care were €5400, €6100 and €4900 (Fig. 2), and 63%, 59% and 51% of these costs were MM-specific, respectively (Fig. 2). The share of outpatient medication costs of all-cause healthcare costs was 41%, 34% and 8% within the last 12 and 6 months of life and during palliative care, respectively. When converting the healthcare costs within the last 12 months of life to costs PPY, total all-cause healthcare costs during the last year of life (€60,000 PPY) were higher compared with total PPY costs accumulated within the first year of MM diagnosis (€53,000 PPY).

The mean all-cause HCRU costs PPM within the last 12 and 6 months of life and during palliative care were €3200, €4000 and €4500 (Fig. 2), with specialized care accounting for 69%, 68% and 44% of the total costs, and 49%, 48% and 54% of the total costs categorized as MM-specific, respectively. The share of MM-specific HCRU costs PPM in primary care were larger during palliative care compared with the last 12 and 6 months before death. In both specialized care and primary care, the total mean PPM costs within all contact categories increased in the last 6 months of life compared with the last 12 months of life. Compared with the 12 and 6 months before death, the mean HCRU costs PPM during palliative care increased in primary care and decreased in specialized care. The highest PPM HCRU cost increase during palliative care compared with the last 12 and 6 months of life was seen in the primary care inpatient stay costs, and the highest reduction was in the specialized care outpatient visit costs. The main cost driver in all analyzed timeframes was inpatient stays (in primary and specialized care combined), accounting for 47% (€1500 PPM), 53% (€2100 PPM) and 67% (€3000 PPM) of total PPM costs for the last 12 and 6 months before death and during palliative care, respectively.

The total mean reimbursed outpatient medication costs PPM for the last 12 months of life were approximately €2000 (or €27,000 PPY), of which lenalidomide accounted for 55%, pomalidomide for 23% and ixazomib for 5% (Supplementary Table 2, see ESM). The respective figures for the last 6 months of life were €2000 PPM, 50%, 24% and 6%. Reimbursed outpatient medication costs during palliative care were €403 PPM, being mainly associated with non-MM medication (lenalidomide was associated with 18%, and pomalidomide and ixazomib with 0%).

3.6 Reimbursed Sick Leave and Associated Costs

The study cohort accumulated a total of 46 reimbursed sick leave days PPY within the first year from diagnosis but the number declined drastically during the following years (Supplementary Table 3, see ESM). During the 5-year follow-up, a vast majority (90%) of sick leave days were associated with MM. It should be noted that the data on sick leave were based on a Kela register on paid reimbursements where sick leave is recorded only after a 9-day waiting period. Thus, these numbers are underestimations as short-term sick leave, lasting 1–9 days, is not accounted for. The mean amount of paid sick leave reimbursements during the first year of diagnosis was €3000 PPY. A significant reduction in paid sick leave reimbursements was seen after the first year with amounts ranging between €136 and €269 PPY during the following years. Reimbursed sick leave days and associated costs were minimal during end of life (Supplementary Table 4, see ESM).

4 Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study with 1615 newly diagnosed patients receiving treatment for MM in Finland during 2015–2020, we demonstrated that the total HCRU and healthcare costs were the highest in the first year after diagnosis and at the end of life. During the 5-year follow-up, the share of reimbursed outpatient medication was on average around half of the total healthcare costs, being the lowest in the first year after diagnosis and the highest in the fifth year after diagnosis. Moreover, we observed that the treatment of MM in Finland is highly focused on specialized healthcare, but at the same time patients are heavily treated in the primary care setting as well. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive nationwide study based on Finnish national healthcare registries assessing all-cause and MM-specific HCRU and costs for patients with MM. Distribution of healthcare contacts between primary and specialized care, utilization patterns over time, or end-of-life costs among MM patients have not been described previously in Finland.

Our observation that healthcare costs of patients with MM were the highest during the first year after diagnosis and during the end of life supports the results of prior research on MM and other malignancies [4, 6, 17, 18]; however, direct comparison between studies is difficult due to differences in methodology. The higher costs during the first year after diagnosis may be partly explained by more active treatment, including SCT and medications requiring administration in hospital. A single-center study of patients with MM in Finland demonstrated that the mean number of visits to specialized healthcare units for infusion medicines was higher compared with that observed for oral treatments [19]. In our study cohort, 30% of patients received SCT within the first year after diagnosis and, based on a subset of the cohort, 72% were administered bortezomib in hospital within a median of 15 days from diagnosis [2]. Accordingly, the trend in costs was clearly generated through the higher MM-specific specialized care costs during the first year after diagnosis compared with the following years. Particularly, the number of inpatient stays in internal medicine wards, where hematological cancers are mainly treated in Finland, seemed to reduce after the first year from diagnosis (data not shown).

We demonstrated that healthcare contacts increased in all contact categories relatively during 6 months before death compared with 12 months before death. Healthcare contacts further increased during palliative care in the primary care setting, but not in specialized care, indicating that, near a patient’s end of life, the focus shifts to primary care setting as patients are no longer actively treated for MM. The focus shift to the primary care setting is most likely explained by patients’ advanced age and the increased need for home care. Although MM-specific resource use decreases towards death, previous studies have shown that the end-of-life costs of patients with MM or other malignancies are higher compared with non-cancer patients [18, 20].

Our estimate of the mean HCRU costs PPY over the 5-year follow-up period was comparable to a previous estimate for patients with MM from one large hospital district in Finland [11]. More specifically, Vikkula et al. reported mean HCRU costs PPY of €33,000 and €20,000 for SCT-treated and non-treated patients, respectively. As 34% of the patients in that study were treated with SCT, the weighted average costs PPY equal those observed in this study (€25,000 PPY). A recent French study estimated the mean annual per-patient healthcare costs at €58,000 [7]. When combining all considered cost elements (including healthcare costs and sick leave) during the 5-year follow-up in the current study, total costs were estimated at €48,000 PPY. The difference in the estimated costs may be partly explained by differences in the follow-up times (22 months vs 31 months) and included cost elements. Specially, we were not able to include disability pensions in our analyses. Thus, we have most likely underestimated the costs due to productivity losses, since 30% of the identified patients were of working age at the time of diagnosis (under 65 years of age).

A Finnish cross-sectional study showed that the average share of hospital and outpatient medication in 2014 was around 30% of total costs, and costs varied across different cancer sites [21]. In our study with newly diagnosed MM patients, the reimbursed outpatient medication costs solely comprised 29% of the total observed costs in the first year, and the share increased up to 59% during the following years. During our study period, most of the novel MM treatment options introduced to treatment practice and to earlier lines of treatment were reimbursed outpatient medications. During the last 12 and 6 months of life, the share of reimbursed outpatient medication costs was 41% and 34% of the total costs, respectively, but <10% during palliative care. In summary, when considering the total cost, key cost drivers seem to be specialized care services during the first year, reimbursed outpatient medication costs during the following years and inpatient stays during palliative care. In the analysis regarding the last 12 or 6 months of life, the costs were distributed more equally across cost elements. The effect of reimbursed outpatient medication costs on the total costs, however, should be interpreted with caution. Reimbursed MM-specific outpatient medication costs may be overestimations as the three main cost drivers of the medication costs, lenalidomide, pomalidomide and ixazomib, were reimbursed under confidential financial agreements in Finland. This means that their total costs to society were lower than reported in this study. For future considerations, it should also be noted that the prices of lenalidomide products, which accounted for most of the costs of reimbursed outpatient medicines during this study period, have reduced by up to 98% after the loss of exclusivity and becoming generic in 2022 in Finland [22].

Our study highlights the importance of looking at all aspects of real-world data within a healthcare system and in a disease that mainly affects older people with multimorbidity. Although the treatment of MM in Finland is highly focused on the specialized healthcare, a majority of all-cause healthcare contacts of the patients with MM were captured in primary care, and only a small fraction of those contacts was MM-specific. This reflects the fact that patients with MM often have comorbidities that do not require treatment in specialized care. When considering only all-cause healthcare contacts, it is highly likely that HCRU directly related to the disease would be overestimated. Conversely, by collecting data on MM-specific events only, the holistic burden faced by patients with MM, especially in the primary care setting, would be underestimated.

Providing healthcare has an opportunity cost [23]. In healthcare systems with a fixed budget, this cost represents the health benefits forgone from other healthcare services that could have been provided with the same level of investment elsewhere in the system. Well-established methods of economic evaluation are used in many countries to inform decisions about the funding of new medical interventions [24]. New treatment options for MM are often first introduced as a later-line treatment option, and thus the corresponding economic evaluation is performed in heavily pre-treated patient populations with relatively low life expectancy and limited treatment options. The information provided in our study can be utilized as the most up-to-date information related to MM and to characterize patients’ end-of-life care in health economic evaluations. After the new social and healthcare reform in Finland, wellbeing services counties need to think more thoroughly about how to produce all statutory services with a fixed budget and already strained resources without compromising better outcomes for the patients. Our study highlights the fact that the HCRU and costs associated with the treatment of patients, especially if old and having multimorbidity, cannot be examined solely from a narrow disease-specific or organizational point of view.

The main limitations of this study are related to how administrative data were used for measuring clinical events and HCRU. First, initiation of palliative care was identified using diagnosis codes recorded in Hilmo. Based on clinical knowledge, it seems likely that both the occurrence of palliative care and its duration were underestimated, which may have further led to underestimation of HCRU and costs associated with palliative care. Second, MM-specific HCRU was identified using ICD-10 code C90.0 as the primary diagnosis. It is possible that not all MM-related contacts had C90.0 as a primary diagnosis code, which may have led to underestimation of the share of MM-specific HCRU and respective costs. For example, infections and skeletal issues may be coded with other ICD-10 codes even if the events were related to MM or its medication. Third, as patient-level data on medicines administered in hospitals were available merely for a subset of MM patients and these data were not comprehensive nationwide nor over time [2], no analyses by treatment lines could be conducted. Although the unit costs for outpatient visits and inpatient stays in specialized care include in-hospital medication costs, no detailed, per-medication analysis for costs were possible. Fourth, when using administrative data, some inaccuracies and missing data are unavoidable. While the validity and accuracy of the Hilmo data has been shown to be very good [25], no validation studies are available concerning AvoHilmo, which was a relatively new register during the study years. Fifth, as data on the contact type was missing for about half of specialized care contacts in 2019 and for 85% in 2020, we used imputed data when estimating the mean numbers of each contact type PPY in specialized care. To evaluate the validity of our imputation, we conducted a complete case analysis. In this analysis, the contact type distribution remained the same as in the imputed analysis for each of the 5 years of follow-up (data now shown). Finally, due to lack of a control group without MM, the incremental costs of MM could not be determined in this study. This study did not address potential differences in HCRU and costs across patient subgroups either.

5 Conclusions

During active treatment (i.e. before palliative care), MM in Finland is primarily treated in the specialized care setting, with outpatient medication and visits to specialized care being the main cost drivers. The total HCRU is higher during the first year after diagnosis compared with the following years and increases towards the end of patients’ lives when the focus shifts to the primary care setting. The results of this study can be used to inform decision makers in local welfare service counties, hospitals and HTA bodies on the holistic real-life HCRU and cost burden associated with the treatment of patients with MM. Specifically, these results can help to estimate the need for care and expected costs over time for newly diagnosed patients receiving treatment for MM. In addition, the results can be used to inform health economic evaluations of MM.

References

Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020;10(9):94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-00359-2.

Ruotsalainen J, Lehmus L, Putkonen M, et al. Recent trends in incidence, survival and treatment of multiple myeloma in Finland—a nationwide cohort study. Ann Hematol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-023-05571-1.

Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating health care costs related to cancer treatment from SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014.

de Oliveira C, Pataky R, Bremner KE, et al. Phase-specific and lifetime costs of cancer care in Ontario, Canada. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):809. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2835-7.

Laudicella M, Walsh B, Burns E, Smith PC. Cost of care for cancer patients in England: evidence from population-based patient-level data. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(11):1286–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.77.

Bugge C, Brustugun OT, Sæther EM, Kristiansen IS. Phase- and gender-specific, lifetime, and future costs of cancer: a retrospective population-based registry study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(26): e26523. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026523.

Bessou A, Colin X, De Nascimento J, et al. Assessing the treatment pattern, health care resource utilisation, and economic burden of multiple myeloma in France using the Système National des Données de Santé (SNDS) database: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Health Econ. 2023;24(3):321–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01463-9.

Hannig LH, Nielsen LK, Ibsen R, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Kjellberg J, Abildgaard N. The impact of changed treatment patterns in multiple myeloma on health-care utilisation and costs, myeloma complications, and survival: a population-based comparison between two time periods in Denmark. Eur J Haematol. 2021;107(1):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/EJH.13615.

Neves M, Trigo F, Rui B, et al. Multiple myeloma in Portugal: burden of disease and cost of illness. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39(5):579–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00993-5.

Koleva D, Cortelazzo S, Toldo C, Garattini L. Healthcare costs of multiple myeloma: an Italian study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011;20(3):330–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01153.x.

Vikkula J, Uusi-Rauva K, Ranki T, et al. Real-world evidence of multiple myeloma treated from 2013 to 2019 in the hospital district of Helsinki and Uusimaa, Finland. Future Oncol. 2023;19(30):2029–43. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2023-0120.

Bennink C, Westgeest H, Schoonen D, et al. High hospital-related costs at the end-of-life in patients with multiple myeloma: a single-center study. Hemasphere. 2023;7(6): e913. https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000913.

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Wellbeing services counties. https://stm.fi/en/wellbeing-services-counties. Accessed February 29, 2024.

Ludvigsson JF, Appelros P, Askling J, et al. Adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index for register-based research in Sweden. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13:21–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S282475.

Mäklin S, Kokko P. Terveyden- ja sosiaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2017. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos (Institute of Health and Welfare). 2021. https://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/142882. Accessed 19 Jan 2024.

Statistics Finland. Price index of public expenditure, PxWeb. https://pxdata.stat.fi:443/PxWebPxWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__jmhi/statfin_jmhi_pxt_11m2.px/. Accessed July 31, 2024.

Seefat MR, Cucchi DGJ, Groen K, et al. Treatment sequences and drug costs from diagnosis to death in multiple myeloma. Eur J Haematol. 2024;112(3):360–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.14119.

Bhattacharya K, Bentley JP, Ramachandran S, et al. Phase-specific and lifetime costs of multiple myeloma among older adults in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7): e2116357. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16357.

Torvinen S, Vihervaara V, Miettinen T, et al. Multiple myeloma treatments, outcomes, and costs of health care resource utilisation during 2009–2016, based on multiple data sources from a hospital district in Finland. Int J Clin Exp Med Sci. 2021;7(1):21–30. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijcems.20210701.14.

Vestergaard AHS, Ehlers LH, Neergaard MA, Christiansen CF, Valentin JB, Johnsen SP. Healthcare costs at the end of life for patients with non-cancer diseases and cancer in Denmark. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7(5):751–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00430-1.

Torkki P, Leskelä RL, Linna M, et al. Cancer costs and outcomes for common cancer sites in the Finnish population between 2009–2014. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(7):983–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1438656.

Yhden syöpälääkkeen hintakilpailu säästi kymmeniä miljoonia—lääkkeiden patenttisuojien päättymisessä on lähivuosina suuri säästöpotentiaali. KELA | FPA. https://www.kela.fi/mediatiedotteet/5264836/. Accessed February 29, 2024.

Hernandez-Villafuerte K, Zamora B, Feng Y, Parkin D, Devlin N, Towse A. Estimating health system opportunity costs: the role of non-linearities and inefficiency. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2022;20(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12962-022-00391-y.

Soares MO, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K. Health opportunity costs: assessing the implications of uncertainty using elicitation methods with experts. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(4):448–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X20916450.

Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812456637.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was funded by Pfizer Oy.

Conflicts of Interests

MK and LL are employed by Pfizer Oy and own Pfizer stocks. RM is a former employee of Pfizer Oy and owned Pfizer stocks at the time of this work. JR, AK, PR, MJK and TP are employees of Oriola Finland Oy, which received funding from Pfizer Oy in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Ethics Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This register-based study was approved by each register holder.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication (from Patients/Participants)

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Research data are not shared. The data are available with the permission of The Finnish Social and Health Data Permit Authority. Thus, the data are not publicly available.

Code Availability

The code used in the data management and analysis can be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Author Contributions

MK, JR, RM, LL, MJK and TP contributed to the study design and objectives, interpretation of results and revising the manuscript. AK and PR were responsible for data analysis. MK and JR were responsible for manuscript development. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosunen, M., Ruotsalainen, J., Kallio, A. et al. Healthcare Resource Utilization and Associated Costs During the First 5 Years After Diagnosis and at the End of Life: A Nationwide Cohort Study of Patients with Multiple Myeloma in Finland. PharmacoEconomics Open (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00524-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00524-4